"Religion is man-made. Even the men who made it cannot agree on what their prophets or redeemers or gurus actually said or did. Still less can they explain why the same god should be so variously and contradictorily worshiped. And all the time, the comforting and bland assurances of religion are repeatedly contradicted by the cruel realities of human suffering, disaster, and injustice.” Christopher Hitchens' God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything.

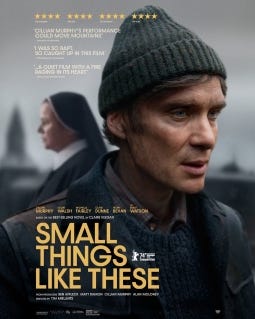

Small Things Like These (movie poster)

As I read Small Things Like These, the themes of moral integrity, personal responsibility, gender and power, religion and hypocrisy, the weight of silence, memory, courage, and economic pressures—resonated deeply. They weren’t just abstract ideas; they resurfaced questions I often wonder about when I read a book like this one, or when I’m alone. Would I have the strength to speak up in the face of injustice? Could I risk my own comfort and security to stand up for what’s right? Questions that we all face when life puts us to the test. What are we truly made of?

That’s why I decided to write my first Substack post on one of these themes. Though I’d love to write a review on all of Keegan’s book, this one has always pulled at my heartstrings: the duality of religion and its hypocrisy, a topic I’ve been running into for the past ten years.

Set in the small Irish town of New Ross in 1985, Small Things Like These centers on Bill Furlong’s discovery of abuse within a local convent-run laundry—a discovery that forces him to confront the dual nature of religious authority in his community, and his own morality.

Keegan masterfully captures the paradox of religious authority through the community’s perception of the nuns. She writes:

"It was hard not to think of the religious sisters as good women, doing their best for the poor and unfortunate. Everyone in the town looked up to them. Their reputation as pious, charitable figures kept them beyond reproach. And yet, behind those walls, it seemed as if a great secret was being carefully guarded."

Through this passage, Keegan subtly exposes the darker truth hidden behind the convent’s walls. What looks like charity and goodness on the surface can sometimes mask something much more troubling, highlighting the way religion in the town functions as both moral authority and tool of oppression.

Magdalene Laundries in Ireland

The novel draws clear parallels to the real-life Magdalene Laundries, one of Ireland’s laundry institutions that claimed to provide aid to vulnerable women and girls but instead subjected them to slave-like conditions. These institutions thrived between 1765 and 1996, sustained by a deeply ingrained culture of secrecy and silence within Irish society. Many survivors of the Magdalene Laundries have spoken about similar abuses to those depicted in Keegan’s novel.

For example, women were often forced to labor without pay (like the young girl Bill finds in the convent) and were told their suffering was part of their penance and path to spiritual redemption. Much like the fictional town, real communities were reluctant to speak out against the Church, allowing the laundries to perpetuate abuse for many years.

The glorification of suffering by religious institutions, unfortunately, isn’t unique to to this time or place. At 23, my now-husband introduced me to the world of Christopher Hitchens, whose critique of institutionalized religion helped me see this pattern in real life. Hitchens often argued that religious institutions preach morality while quietly enabling systemic abuses. In The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice, Hitchens critiques Mother Teresa’s organization for focusing on the spiritual side of suffering while neglecting basic healthcare needs. Rather than using the considerable donations the Missionaries of Charity received to improve medical care or provide adequate comfort for the poor, the organization focused on preparing people for death and encouraging them to accept their suffering as a path to spiritual salvation. Hitchens points out that Mother Teresa herself believed suffering brought people closer to God, and this belief translated into a neglect of pain relief and proper healthcare for the sick and dying in her care. He saw this as a reflection of the broader moral contradictions within religious institutions—where spiritual salvation takes precedence over addressing real-world suffering.

Keegan’s Small Things Like These mirrors this idea: the hypocrisy of the Church is clear. The same nuns who publicly represent charity and humility are complicit in a hidden system of abuse. Through their actions, Keegan exposes the moral contradictions that Hitchens so often pointed out in real life.

Over the years, I’ve heard people claim that morality stems from religion—that without it, we would have no moral compass. But I challenge you to reflect on the idea that true morality is born from individual responsibility, not from religious dogma. This is also the challenge Keegan offers us through her book. Bill Furlong’s decision to follow his moral instincts, rather than bow to the Church’s authority, echoes Hitchens’ belief that real moral action comes from rejecting institutional hypocrisy and taking personal responsibility.

Why is this important? Because this distinction between individual responsibility and institutional morality is crucial; it shifts the focus from blind obedience to active moral agency. When morality is tied solely to institutions, particularly religious ones, it becomes vulnerable to the flaws and corruption of those institutions.

Finally, while I understand the theological belief in the redemptive power of suffering, Keegan’s Small Things Like These critically examines this idea, showing the darker consequences when suffering is glorified to justify abuse, exploitation, and the neglect of basic human dignity. The book reminds us that we all have a choice: do we turn a blind eye to injustice, or do we take responsibility, even when it’s uncomfortable? In a world full of institutional failings, perhaps our greatest power lies in our individual acts of courage. Small things like these are what makes a life whole.

Ship of Fools by Hieronymus Bosch

What do you think? Have you ever experienced moments where personal morality clashed with institutional authority? I’d love to hear your thoughts.